Installing the future

According to Brian and Leland Maschmeyer, Chobani chief creative officer and co-founder of COLLINS, great designers don’t invent the future. Instead, they sense where the world is going and what it needs, and install that future for the rest of us.

But despite this power to influence daily life and the richness of design’s heritage, we seem to have traded big, inspiring visions of the future for the crutch of increasingly popular, easy-to-sell, one-size-fits-all processes.

“Search the word ‘designing’ and the internet throws up endless dreary photographs of people playing with tiny, multicolored sticky notes,” says Brian. “Design reduced to a generic, commoditized process. Dumbed-down rules. Empathize! Ideate! Prototype! It’s easy. Simply rinse and repeat.”

This not only risks belittling the purpose of design, it also turns our potential contribution into something far less meaningful and influential than it could — and should — be.

However, Brian and Leland believe it’s time for designers to reclaim their imaginative, soulful connection to the future and how it’s built.

Reconnecting with tomorrow

To reinterpret the future for their own work, Brian and Leland looked to the past, trying to determine the last time a collective, energized, creative force captured the spirit of tomorrow. The answer: NASA in the 1960s.

“One of the things that has most fascinated us as a culture and a society has been space,” says Leland. “But our relationship with space travel before the 1960s was never focused.”

Initially, “space” was a place in our collective imaginations for adventure, flying saucers, and alien encounters. However, after a series of successful efforts by the Soviet Union to conquer space during the late 1950s, space became the front line of the Cold War.

America responded quickly, fueling the “Space Race” by launching NASA. But when President John F. Kennedy arrived, he reframed the threat with a different story — one of humanity’s exploration of a “New Frontier.” Suddenly, space became a place for discovery, not war. Astronauts would set sail into a “sea of peace,” full of opportunity and benefit for all of humankind.

To expand this narrative and capture the imagination of the country, NASA smartly drew from a range of archetypes, and tapped talented designers to express them. For example, images of the first astronauts closely mirrored portraits of early European explorers to promote the idea of scientific discovery. Those iconic silver space suits deliberately pulled from the mythos of 1950 science fiction heroes. Even something as small as mission patches on space suits were thoughtfully designed to embody the spirit of bringing peace to the stars.

“As NASA was putting man on the moon, the creative class was putting everyone else out into the galaxy and into the stars,” says Leland. “It was a collective effort, binding all these narratives and forces together — making the New Frontier tangible in people’s everyday lives.”

Designing for the future you want

Facilitating these kinds of collective efforts can start new conversations in our design culture and change the way we think and design for the future.

“What’s particularly interesting about this to Brian and me is that when you start dialing back and take the specifics out of it, you see the future itself more as a framework or a construct,” says Leland. “What you get is six really interesting elements to start thinking about the future and how to bring it about.”

These elements can be broken into two levels. The first three elements form the core:

-

Means: a technological force of change that is feasible and possible.

-

Want: an immediate, motivating desire.

-

Belief: the higher order ideal that motivates the change or action.

In order to link the core elements, you need three connecting elements:

-

Story: a playbook for action that lets you know where it’s going.

-

Symbols: the visual language that carries meaning and lets you see the future.

-

Systems: the tools that let you touch and live the future.

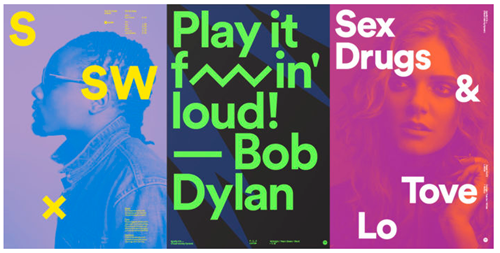

For example, when Brian and Leland began working with Spotify, it was a strong, thriving product, but it wasn’t a strong brand… yet.

Spotify’s origins had a means — the streaming technology itself. It had a want — the music people desired. And it had a driving belief — the leaders at Spotify wanted to help reinvent and support the music industry.

After watching how earlier streaming service models had failed artists and musicians, Spotify believed it could do better, and could pay musicians for their streams. All of these elements shifted a dramatic identity shift, evolving Spotify from looking like a tech startup to behaving like a music company — and help usher in “the sound-tracked life.”